Foster's Mill

Foster's Mill, located between Horbury and Ossett in Yorkshire, England, was a major cotton and wool spinning textile mill, and one of the first to install steam engines in the late 18th century.

The mill building was built in the mid-18th century for the Foster Family, but was completely destroyed by the Luddites in the early 19th century, who attacked textile machinery in protest against the Industrial Revolution.

Origins & History

Foster's Mill was built around 1750 for Joseph Foster (1693-c.1790), a wealthy wool manufacturer committed to Ossett's social and religious causes. While the construction of this textile mill significantly increased production, it took place near the beginning of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) and at a time when many people in Ossett were still producing woolen fabrics at home with weaving machines.

According to Mayall's Annals of Yorkshire (1734-1736), "The inhabitants of Ossett, a village three miles from Wakefield, have been employed in making broad woollen cloth from time out of mind." "Wool spinning and cloth making were originally important as cottage industries."

At the end of the 18th century, some artisans who had been able to buy a machine accumulated small surpluses of capital and invested them in the incipient industry, acquiring new machines. The competition between these first industrialists demanded technical improvements that allowed to manufacture faster and cheaper. This demand caused a cascade of inventions that multiplied production capacity, especially highlighting the use of the steam engine in those early factories, which aroused hostility from spinners and weavers because it reduced the necessary labor, leading to the emergence of a movement that protested the degradation of their living and working conditions.

According to R.L. Arundale in Proud Village, A History of Horbury in the County of Yorkshire, "At the start of the Industrial Revolution steam engines were installed at Race's Mill in Dudfleet and Foster's Mill on Engine Lane in 1795."

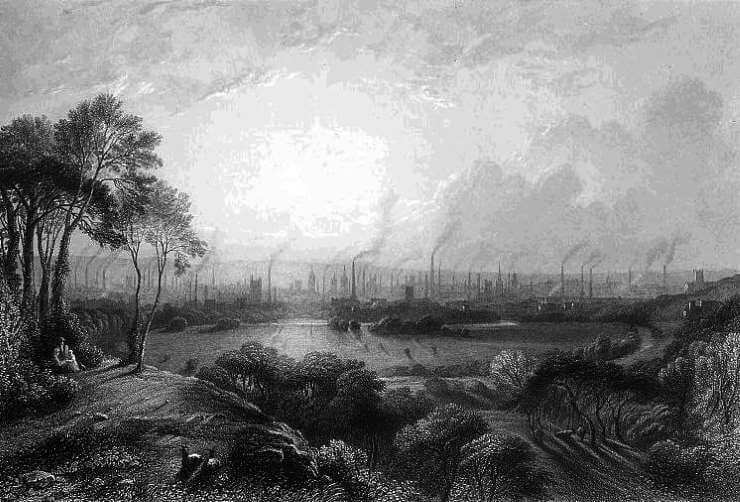

Starting in 1780, more powered mills running on steam engines began to appear in Ossett, in turn generated by coal-fired boilers. As a result, it is also not surprising that during this time this village was a place that lacked smoke-free zones.

Every respectable Ossett textile mill had a chimney and usually a mill dam too. So numerous and prominent were these huge brick structures that you might think that there had been a competition among those pioneering Ossett businessmen to see who could build the biggest and best mill chimney. However, the smoke pollution from the mill chimneys was a constant nuisance and several Ossett mill-owners were prosecuted in the 19th century because the smoke from their mill chimneys was regarded as a public nuisance.

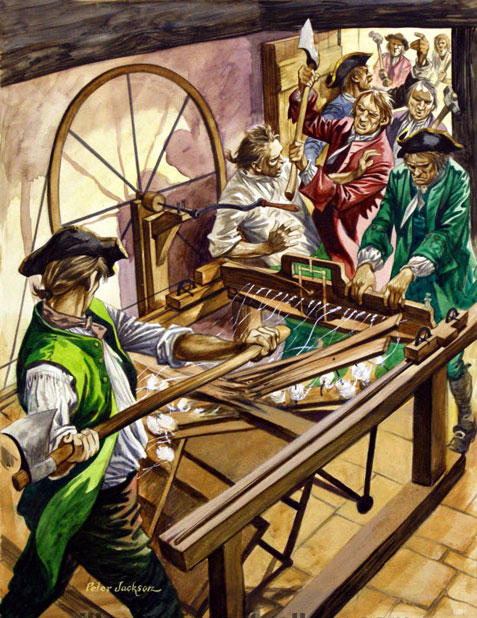

Foster's Mill stood for many decades until April 9, 1812, when a crowd of three hundred Luddites from the Spen Valley, West Yorkshire, armed with firearms, axes and clubs, caused extensive damage to machinery and property by destroying this and other factories, their shearing and weaving structures, along with a series of windows.

This imminent attack perpetrated by this secret organization based on the oaths of 19th century English textile workers destroyed the textile machinery through protest. They rebelled against manufacturers using machines in what they called "a fraudulent and deceptive way" of circumventing standard labor practices.

Luddites gathered at night on the moors surrounding industrial cities for military exercises and maneuvers. It's main areas of operation began in Nottinghamshire in November 1811, followed by the West Riding of Yorkshire in early 1812, and then Lancashire in March 1813.

Over the years there would be sporadic outbreaks of violence in various forms, not always related to factory work, but in retaliation for the industrialization process that affected many established traditions and practices. The Luddites were the pioneers in this fight against the machinery that replaced the work of men.

"Resistance to the implementation of new textile machinery and the factory system was shown when Luddites, who blamed the new factories for depriving weavers from earning a living in a time of widespread hunger and poverty, destroyed Foster's Mill."

On that fateful April 9, 1812, hundreds of people armed with "hatchet, pike and gun" destroyed the dazzling mills and razed Joseph Foster's (1693-c.1790) mill. Before the introduction of machinery, cultivators were well-paid skilled men, but they were quickly reduced to misery after this.

As early as 1778 there was some episode of destruction in the Lancashire region of the largest spinning machines, reducing wages and undermining the skills of craftsmen who knew the trade well; the latter saw how the knowledge of their profession, carefully acquired, did not serve them to compete with machines that multiplied production.

Royd's Mill

Royd's Mill, previously known as Foster's Mill on Leeds Road was often described as a "the cotton mill" since, when it had opened in the 1820s, it had been used for cotton spinning and weaving, which was unusual for Ossett.

In 1826, the mill was occupied by Robert Blakey and son, and they had obviously recently had a steam engine installed because they were advertising for person, preferably a smith, who understood the firing and working of steam engines to look after a 36 horsepower engine made by the Low Moor Company of Bradford.

Applications were to be made to Robert Blakey and son, Streetside, Ossett. However, this must have been in vain because only five months later, Robert Blakey and Samuel Blakey of Ossett, cotton spinners and calico manufacturers were bankrupt.

The mill was four storeys high, 72 yards by 15 yards with good attics. It's machinery was manufactured by Bayley & Co. Machinery and included fourteen throstles with 2,100 spindles, sixty power looms, and eight mules with 2,704 spindles.

By 1829/30 the owner and occupier of Royd's Mill was William Hanson and sons. However, the mill had been taken over in 1832 by Collett & Smith and they were still there in 1842.

The partnership of William Hanson and sons was dissolved in early 1832, which probably precipitated their sale of Royd's Mill. In fact, Thomas Collett was a machine maker in Streetside, Ossett, but was also a partner in Collett & Smith, who continued to make cotton cloth at Royd's Mill. Operation of the mill was disrupted in 1832 by a fire8 and then in 1833, the mill was completely destroyed by a more serious fire.

In 1843 and 1844, the mill was empty, but was now owned by Joshua Whitaker (1804-1882), possibly the Ossett malster who built Croft House. An advertisement for the sale or let of the substantial mill on Ossett, Street Side appeared in the local press and it appears that after the fire in 1833, the mill was completely rebuilt because it was no five storeys high and 26 yards long by 14½ yards wide. There was a wooleying house at one end with a chamber over together with a blacksmith's shop, 38 horsepower steam engine and two boilers, supplied with excellent water. There were also two houses next to the mill; one described as being suitable for a respectable family and the other suitable for the manager.

The mill was sold to George Foster and he is noted as the owner and occupier in 1851 having bought the mill in 1845. In 1847, the company was listed as Foster and Co. scribbling and fulling millers so the usage of the mill had changed after the demise of the Collett & Smith business enterprise.

In 1853, the ownership of the mill changed again and it was owned by Robert W. Simpson. However, by 1857 this had changed again and John Lee and Sons, who were blanket manufacturers had taken over the mill.

The company were fined £3 plus expenses under the terms of the Factory Acts for not lime washing the mill walls. Also Lee, Scott and Fenton, Royds Mill, Ossett were fined £2 plus expenses for employing young persons without a surgeon's certificate.

In December 1860, a fire attended by five fire engines caused considerable damage to a two-storey mill 40 yards long at the Royds Mill premises of Messrs. Lee, Scott & Fenton, the joint proprietors.

The mill was completely gutted with the roof and floors falling in at the height of the blaze, destroying machinery and woollen material. The total loss was between £2,000 and £3,000 and was fully insured.

In 1875, there was a strike of willeyers, fettlers and feeders at Royds Mill who wanted wages at the old rate, but with a small reduction in hours. In the event, Messrs. Lee made the desired concession and it was expected that other local mill owners would follow suit. However, by 1877, it was reported that the business of John Lee & Sons, blanket manufacturers, Ossett, Streetside and Earslheaton had failed.

In August 1878, there was an auction advertisement for the sale of the machinery and stock-in-trade of Royds Mill.

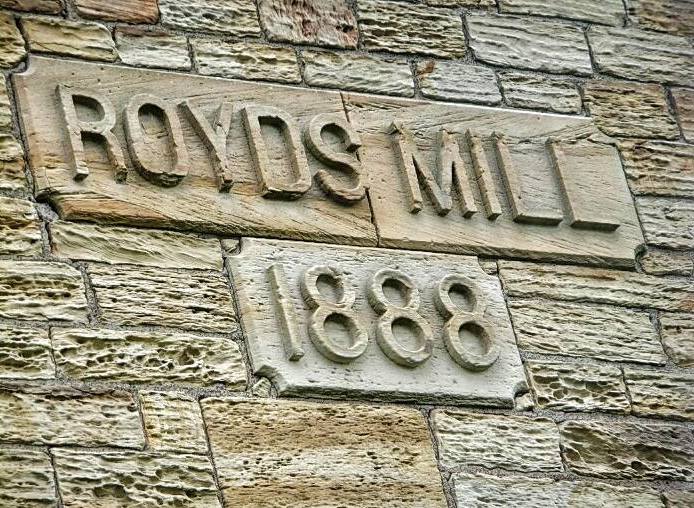

By 1879, after John Lee's business failed, the mill was bought by George Hanson (1837-1893) and Henry Wormald, two local men from Gawthorpe. At some time after 1854, the name of the mill was changed to Royds Mill. However, some of George Hanson's ancestors had owned the mill a generation or two previously, presumably between 1829-1832, when the mill was owned by William Hanson & Sons.

Hanson and Wormald had started their partnership in March, 1875 as rag and mungo merchants, first renting rag-pulling machinery at Greengates Mill, Chickenley Heath and then moving to Greaves Mill at Gawthorpe.

George Hanson was the senior partner with Henry Wormald in their business concern at Royds Mill, which they operated as woollen rag and mungo merchants, buying in huge stocks of rags. In 1881, they employed 25 men and 90 women as mungo manufacturers, letting part of their extensive premises to other manufacturers. In 1881, there was an advertisement to let at Royds Mill a detached mill or warehouse some 90ft square and three-storeys high with a dyehouse and a dryhouse plus crane.

Like many of the other mills in Ossett, Royds Mill was troubled by fires and in October 1881, they experienced a fire on the premises, the first of several more to come.

Royds Mill itself had been extended several times from a single mill building running parallel with Leeds Road before it was bought by Hanson and Wormald and they were granted planning permission in 1884 to build a new extract plant. There were still tenants at Royds Mill in 1884, despite Hanson & Wormald's burgeoning business and the failure of one of these tenants, Alfred Blakeley, cloth manufacturer of Chickenley Lane was noted in the local press.

By 1887, there were three large mill buildings; two were four-storeys high and one three-storeys high with additional offices, stables, dye-house and an engine house complete with a 300 horse-power, steam-powered, condensing beam engine and two Cornish boilers with a dry-house over the top of them.

Disaster struck on September 6th 1887 when fire broke out during the night in a rag warehouse at the mill. This was at a time when they had a higher stock of rags than ever before, having availed themselves of recent price fluctuations in the market to buy heavily. The bales of rags were piled up from floor to ceiling on the first and second floors in two of the large mill buildings and in all there were hundreds of tons of rags in the mill buildings.

Sadly, because of the prevailing drought in the summer of 1887, the water supply to Gawthorpe was turned off overnight. For over an hour, there was no water for the high-pressure hosepipes and the fire very quickly took hold, completely destroying Royds Mill. It was said at the time to have been the most extensive and rapidly destructive fire ever to have taken place in Ossett within living memory. The fire caused £30,000 to £40,000 of damage if the losses of the other occupants of Royds Mill; Mr Joseph Briggs and Messrs. Briggs and Waterhouse, cloth manufacturers were also taken into account.

About 170 workers were made redundant overnight because of the fire. Part of the gutted building fell into Leeds Road causing it to be closed to traffic and the embers of the building burned for days. However, almost immediately, Hanson and Wormald resumed operations at nearby Greaves Mill, which had been unoccupied fro some time.

By August 1888, Royds Mill had been rebuilt with one storey sheds replacing the previous four-storey buildings, despite only being insured for about half of their considerable £26,000 loss as a result of the fire. A new horizontal 350 horse power steam engine christened "Queen & Empress" was also commissioned during the rebuilding of the mill. By 1893, all the tenants had left the Royds Mill site and it was occupied solely by Hanson & Wormald.27 They were listed in the trade directories of the time as "Hanson & Wormald, rag and mungo merchants, Royds Mill.

Both George Hanson and Henry Wormald were involved in public life and became Mayors of Ossett. Sadly, George Hanson died at the early age of 55 from a bout of pneumonia during his term of office as Ossett's mayor. He was staying at Southport over the Easter holiday in 1893 in an attempt to recuperate from his illness when he succumbed and died. Hanson, a lifelong teetotaller and stalwart of the Zion Congregational Church in Gawthorpe, was also an ex-Chairman of Ossett's Local Board, and was a very popular and well-liked man. He was afforded a public funeral at Holy Trinity Church, Ossett where he was buried with many tributes to his contribution to public life. The "Ossett Observer" said of him in 1889 " Of him it may be said that Gawthorpe never furnished a member more attentive to it's particular interests, or one who took a wider and more intelligent view of local matters generally."

Henry Wormald J.P. (1837-1901) lost his wife Sarah Ann in October 1891 and sadly the couple had no children, so, after the death of George Hanson in 1893, Wormald enthusiastically put his heart and soul into running the business at Royds Mill and he also decided to take part in public life by getting involved with local politics. In 1900, Wormald and Ellen Hanson converted the mungo and rag business at Royds Mill into a (private) limited liability company with £20,000 in £10 shares to carry on the business of manufacturers of and contractors for and dealers in mungo, shoddy, wool, woollens and rags of every description.

A native of Gawthorpe, as a young man, Henry Wormald was a piecener at Royds Mill, when it was a blanket factory and he was subsequently employed in the mungo trade in Ossett and Morley before going into partnership with Hanson. Wormald succeeded George Hanson as councillor for the North Ward in Ossett, being re-elected several times without opposition. He became mayor of Ossett in 1899 and had a reputation for working hard on behalf of the Borough and for his native Gawthorpe. A staunch Congregationalist at the Zion Church in Gawthorpe, Wormald was also president of the North Ward Liberal Club. Wormald had been ill for some time and died on the 16th July 1901. He was buried in the family vault at Holy Trinity Church, Ossett with his wife.

In Popular Culture

The events that happened at Foster's Mill that fateful April 9, 1812 led British folk music vocal group Swan Arcade of Bradford to compose a song in 1976 titled "Foster's Mill." This tune from his album Matchless refers to the 1812 Luddite rebellion at Joseph Foster's (1693-c.1790) mill.

"Come, all you croppers stout and bold, let your faith grow stronger still, for the cropper lads in the county of York have broken the shears at Foster's Mill.

Around and around we all will stand and sternly swear we will, we'll break the shears and the windows too and we'll all set fire to tazzlin' mill.

The wind it blew and the sparks they flew, which alarmed the town full soon, and out of bed poor folk did leave, and they run bi the light o' the moon.

Around and around they all did stand and solemnly did swear, neither bucket nor kit nor any such thing should be of any assistance there.

All dark and dreary is the day when men 'have to fight for their bread; some judgment sure will clear the way and the coach of triumph shall be led."

Swan Arcade - Foster's Mill (1976)

Bill Price (1944-2016), the English record producer and audio engineer who worked with The Clash, The Sex Pistols, and Guns N'Roses also did a Foster's Mill song. This version appeared on his 1972 album "The Fine Old Yorkshire Gentleman".

Luddism

Luddism was a movement led by English artisans in the 19th century, a radical faction that destroyed textile machinery between 1811 and 1816 through protest. Industrial looms and the industrial spinning machine introduced during the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) threatened to replace artisans with less-skilled and lower-paid workers, putting them out of work.

The Luddites feared that the time spent learning the skills of their craft would be wasted, as machines would replace their role in industry.

Although the origin of the Luddite name is unclear, it is believed that the movement took it's name from Ned Ludd, a weaver from Anstey, near Leicester, a young man who allegedly broke two looms in 1779, and whose name became emblematic of the machine destroyers.

Many Luddites owned workshops that had closed because factories could sell the same products for less. But when workshop owners set out to find a job in a factory, it was very difficult to find one because producing things in factories required fewer workers than producing those same things in a workshop. This left many people unemployed and angry.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012) has considered this movement of destruction of machines as a form of "collective bargaining for riots", which would be in this formulation a tactic used in Great Britain since the Restoration (1660), since the expansion of factories throughout the country did large-scale demonstrations impractical.

These attacks against the machines did not necessarily imply hostility towards the machines as such, but were only a convenient target against which an attack could be carried out.

Over time, the term has come to mean one who is opposed to industrialization, automation, computerization, or new technologies in general. The Luddite movement began in Nottingham in England and culminated in a regional rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816.

Mill and factory owners began firing at the protesters, and eventually the movement was repressed with legal and military force.

Luddites, the Great Rebellion of the 19th Century

At the beginning of the 19th century, workers saw their working and living conditions worsen due to the use of machinery in agricultural and industrial tasks, which introduced longer and harder working hours, reduced the demand for labor and imposed lower wages. The response to this was the rise of the Luddite movement, which focused on the destruction of factory machinery.

England mobilized thousands of soldiers to fight them and armed confrontations multiplied. Added to the harsh changes in the work environment and the restriction of political freedoms in 1806 was added the blockade of trade between British and European ports ordered by Napoleon, at war with Great Britain, which deprived the English of many markets, left without It employed many workers and forced many entrepreneurs, deprived of good raw materials by the blockade, to produce lower quality goods.

Then it all exploded in Arnold, a town near Nottingham, the main manufacturing city in central England. On March 11, 1811, in the marketplace, the king's soldiers dispersed a gathering of unemployed workers. That same night, almost a hundred machines were destroyed with hammers in factories were wages has been lowered.

They were spontaneous and dispersed collective reactions, but they did not take long to acquire a certain coherence. In November, in the nearby town of Bulwell, masked men wielding maces, hammers and axes destroyed several looms of the manufacturer Edward Hollingsworth. During the attack there was a shooting that killed a weaver.

It was then that the manufacturers began to receive mysterious missives signed by an imaginary General Ludd. This character gave name to a protest movement that was not centralized, but was the result of coordinated efforts, perhaps suggested by former soldiers, who, in addition to intimidating anonymous letters and pamphlets calling for insurrection, prepared punitive expeditions at night.

The first destruction of an industrial facility occurred on April 12, 1811, when three hundred workers attacked William Cartwright's spinning mill in Nottinghamshire and smashed his looms with their sledgehammers. The small garrison charged with defending the building wounded two young saddlers, John Booth and Samuel Hartley, who were captured and died without revealing the names of their companions.

The same happened to Foster's Mill on April 9, 1812, owned by the Foster family, when a crowd of three hundred Luddites from the Spen Valley, West Yorkshire, armed with firearms, axes and clubs, caused extensive damage to machinery and they destroyed the mill building.

Open War

The activity of the Luddites caused panic among English landowners and big business, who saw the movement as a real danger to their companies and their profits.

The formidable increase in agricultural activity in England in the 18th century provided some families with the prosperity they needed to have a spinning machine at home and supplement their precarious income. But the technical innovations that had allowed that growth in production also left many weapons in the countryside in excess, and those who lost their livelihoods migrated to the ever-growing cities. There, officers and apprentices working in urban shops and businesses saw a flood of homeless peasants looking for work fill the suburbs.

In 1794, the increase in political and social tension led the Government to suspend habeas corpus, a fundamental legal guarantee for detainees. Five years later, the Combination Act 1799 prohibited workers' association, making collective bargaining impossible. It would not take long for the conflict between workers and employers to break out, supported by a state that feared the union of political radicalism and labor demands.

Government Response

In 1812, Parliament passed the Frame-Breaking Act, which punished the destruction of a loom with the death penalty. The opposition was minimal. Lord Byron (1788-1824) denounced what he considered the plight of the working class, the foolish policies of the government, and the ruthless repression in the House of Lords on February 27, 1812: "I have been to some of the most oppressed provinces in Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, have I seen such miserable misery as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country." "Is there not enough blood in our penal code already?"

The British government attempted to suppress the Luddite movement with a mass trial in York in January 1813, following the attack on Cartwrights Mill in Rawfolds near Cleckheaton and although the proceedings were legitimate jury trials, many were abandoned for lack of evidence and 30 men they were acquitted. These trials were definitely intended to act to dissuade other Luddites from continuing their activities. However, the heavy hand did not stop the Luddites, to the point that an army of twelve thousand men was armed to pursue them, at a time when barely ten thousand Englishmen were fighting against Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) on the continent.

This fact shows the terror that the Luddites aroused among the ruling classes. By denouncing the accelerated pace of work that chained them to the machine, the Luddites revealed the other side of technology and questioned technical progress from a moral point of view, defending cooperation over competition, ethics over profit. That is why his attacks were accurate: they broke the machines that belonged to entrepreneurs who produced poor-quality objects, at low prices and with lower wages.

The government's response culminated in a trial in York and the execution of 17 Luddites in January 1813. Months earlier, a series of trials in Lancaster resulted in eight hanged and 17 deported to Tasmania. These harsh sentences of the guilty, which included criminal execution, quickly ended the movement in 1816.

Legacy

In the 19th century, occupations that arose from the growth of trade and shipping in ports, also in "domestic" manufacturers, were notorious for precarious employment prospects. Underemployment was chronic during this period, and it was common practice to retain a larger workforce than was typically necessary for insurance against labour shortages in boom times.

Moreover, the organization of manufacture by merchant-capitalists in the textile industry was inherently unstable. While the financiers' capital was still largely invested in raw material, it was easy to increase commitment where trade was good and almost as easy to cut back when times were bad. Merchant-capitalists lacked the incentive of later factory owners, whose capital was invested in building and plants, to maintain a steady rate of production and return on fixed capital. The combination of seasonal variations in wage rates and violent short-term fluctuations springing from harvests and war produced periodic outbreaks of violence.

Bibliography

- Arundale, R.L. (1951), Proud Village: A History of Horbury in the County of Yorkshire, Horbury and District Historical Society. P. 19.

- Writings of the Luddites edited by Kevin Binfield. 2015.

- The Risings of the Luddites, Chartists and Plugdrawers by Frank Peel. 1880.

This website is developed by Westcom, Ltd., and updated by Ezequiel Foster © 2019-2021.