First Records

There have been a number of explanations as to how the surname Foster originated in England.

The main line is that Foster is a contracted spelling of 'Forester', a term that describes an official in charge of a forest.

In the Middle Ages, forests were almost always owned or controlled by the lord of the mansion. But people had no reservations about sneaking in and grabbing firewood, or whatever else was available. To keep poaching to a minimum, the lord hired a man to observe the forest, often called the Forester.

Sir John Forester (1176-1120), who was recorded in The Pipe rolls or Great Rolls of the Pipe in 1183 from Surrey County, was the first recorded bearer of this time and was honored with the knighthood. Several other members of this distinguished family went to the Holy Land during the Crusades, and the records of this family clearly reveal their bravery and resourcefulness.

After Forester, 'Forster' became the most common spelling and then 'Foster' became established as the most widely used. Hence, 'Great Foresters', originally built as a royal hunting lodge and gracing an estate of over fifty acres in what was once the heart of Surrey's Windsor Forest, is now known as 'Great Fosters'.

However, there is a family lineage of Foster that has been carefully traced up to 1066 times. This Foster family has an ancestry dating back, according to family research, to an early period in Flanders, a historical territory in the Netherlands.

The family's recorded history begins with Anacher (790-837), the Great Forester of Flanders, who married Marie Madinhevn (791-825) in 810 AD in France and had at least one child.

When around 800 AD, King Geoffrey I of Denmark (c.780-810) became oppressive and exacted high taxes from the nobles and their subjects, the Roman Empire was crumbling and could not defend it's provinces and the northern coast Europe, including England and Scotland, was easy prey for these Danish nobles, who conquered much of Germany, France, Spain, Switzerland, and Italy.

One of these nobles, Anacher, acquired large estates near Bruges and Sluys, now in Holland, and organized the conquered territory into a state and made Arras, now in France, his capital of Flanders.

Charlemagne (c.742-814), with the help of Anacher and his army, became the successful defender of Christianity and the Roman Empire from the attacks of the new swarms of Scandinavians, elevated Anacher to a cabinet position that he He called himself as 'Great Forester', because Anacher would take care of all the wild animals and government lands of France.

According to the prominent American genealogist Frederick Clifton Pierce (1855-1904), 'Anacher (790-837), the Great Forester of Flanders was the ancestor of all the Fosters that ever lived.'

The family surname was originally Forester, and according to family accounts, the first man with that name in England was Sir Richard Forester (c.1034-c.1084), who was knighted by William the Conqueror (1028-1087) at the age of 16, and whose sister, Mathilde (Flandre) of England (c. 1031 - November 2, 1083), married the brand new king of Norman origin.

From a young age, Forester joined William the Conqueror, moving from Flanders to England after the decisive Battle of Hastings (October 14, 1066), and is popularly known as the son of Baldwin V (c. 1012 - September 1 1067), descendant of the first Forester, Anacher (790-837).

In 1191, Sir John Forster, first governor of Bamborough (c. 1176-1220) accompanied Richard I, "Richard the Lionheart" (September 8, 1157 - April 6, 1199) to Palestine during the Third Crusade (1187 -1192), saved his life in Acre and was awarded Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland. There the family resided for more than five hundred years. There are also ties with this family to Scotland and Ireland.

Two books relate this ancient story. Dr. Billie Glen Foster published his tome The Fosters Family of Flanders, England and America in 1990 and, as the title implies, extended the family line to early immigrants in colonial Virginia.

The second author is Gerry Forster, whose work 'The History of the Forster Family and Clan', completed in 2003, is available on the Internet. This book is about the Northumberland Foresters and the Scottish Foresters.

A link has probably not yet been established between Anacher, the Great Forester in Flanders, and his Foster descendants in America.

Reginald Foster (1595-1681), one of the earliest immigrants to New England, was once thought to provide this connection. But the English genealogy here seems doubtful.

A more recent focus has been on a Richard Foster who immigrated to Virginia but, unfortunately, there is uncertainty as to which immigrant the Fosters' ancestor was, later in the United States.

Hassell Hall in Ossett / West Yorkshire

The story continues in Ossett, a town within the metropolitan borough of the city of Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, midway between Dewsbury to the west and Wakefield to the east, where the descendants of the ancient Foster family resided for many centuries.

This town of 21,231 inhabitants, is located about 260 km from London and there is some evidence of Roman settlement in the Ossett area, for example, it's said that Roman coins were found in Streetside and Roundwood. More recently, there is also some evidence of Roman settlement in the Gawthorpe area of Ossett.

When the Romans left England around 430 AD, the area was invaded by the Angles, Saxons, and other peoples of northern Germany. This colonization lasted more than 400 years and the invaders killed or drove the previous inhabitants while establishing a firm foothold in what would become Ossett and it's surroundings.

It has been suggested that the variation in the broad local language of the Yorkshire dialect is the result of settlements by different Anglo-Saxon groups.

Ossett, first appears in the Domesday Book of 1086 as "Osleset", which was in the Wakefield mansion, and was compiled for William the Conqueror (c. 1028-1087) that same year.

Hassell Hall

Hassell Hall was an old mansion southwest of Ossett in West Yorkshire, England. The house dates from the 17th century, it was renovated in the 18th century and demolished in the middle of the 20th century.

The mansion was a large stone hall and was built by Mr Richard Foster (c.1648-1730) in 1699, who resided for several years and managed the building for a time.

In 1716, Foster ceded use of the property to his brother-in-law John Lumb of Wakefield (1690-1764), a wealthy wool merchant who built Wakefield's Silcoates Hall in 1748.

It's suggested that the house was originally oriented to the west and that consequently the old door was at the rear of the subsequently renovated building.

The lintel of the main entrance was engraved with the initials F.R.H. and the date 1699, which referred to "F" for "Foster", "R" for "Richard" and "H" for "Hannah", his wife's name.

When the building was demolished in 1961, the stone was used to build the cabin at the entrance to the park, now known as Green Park, an area of open green space on the northwest side of Horbury.

Foster & Lumb from West Riding of Yorkshire

In Ossett, around 1648 was born Mr. Richard Foster (c. 1648 - September 17, 1730), an independent dissident and cloth merchant, persecuted for his beliefs until his death in 1730.

He was the son of Dame Foster (1614-2 February 1709) and Richard Foster (1623-20 September 1710), both of Ossett. His parents married around 1648 at a time of great change as a result of the reign of Henry VIII of England, and together they had at least one child.

Richard Foster married Hannah Burnet Jackson (1658-1724) on January 23, 1687 in Bilston and together they had 7 children: Stephen Foster of London (1682-1719), Joseph Foster of Ossett (1693-?), Richard Foster of Flanshaw Lane (1686-1729), Hannah Foster (1674-1763), Benjamin Foster of New York (1699-1735), Elizabeth Foster (c.1685-1740) and Mary Foster (1693-1760).

The Nonconformist Register, the register comprising numerous notices of Puritans in and around Yorkshire, started by Oliver Heywood (1630-1702) and continued by the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743), describes Richard Foster as follows:

'Mr. Richard Foster of Ossett, my dear and honorable father-in-law, died on September 17 after suffering severe strangulation pain for a considerable time, he had been of great help as a Christian and as a merchant.'

Another carefully treasured document that has been passed down through the generations is a letter written by his son-in-law, Thomas Dickenson, to his granddaughter in 1731 that references his father-in-law Richard Foster:

'He feared God from his youth and over many, surpassed many others in gifts and knowledge, and God honored him by making him eminent in grace and usefulness as well. He was a solid and judicious Christian, strictly pious and devoted in his duty to God, and conscientious in his dealings with men. Although he lived a considerable time and had a lot to do with men and business, he has left a good name, a righteous character behind him.

He was very careful to instruct his family in the things of God, keeping religion and the worship of God constantly in his home, as well as diligently attending to public ordinances. He was an exceedingly caring and forgiving husband, a loving and tender father, a good master and a helpful neighbor, and I am convinced that he will be greatly missed in this place, for there are few like-minded so capable and willing to give themselves for God.

He was a great tribute to the good men and ministers of both denominations, conformists or non-conformists, being ready at all times to support and encourage them. But now he rests from his works, and his good works follow him, in the blessed reward and the rewards of glory.'

Richard Foster died after suffering severe strangulation pains for a considerable time, on September 17, 1730, in Ossett, and was buried in Horbury Cemetery in Wakefield, England.

Congregational Chapel on The Green / Ossett

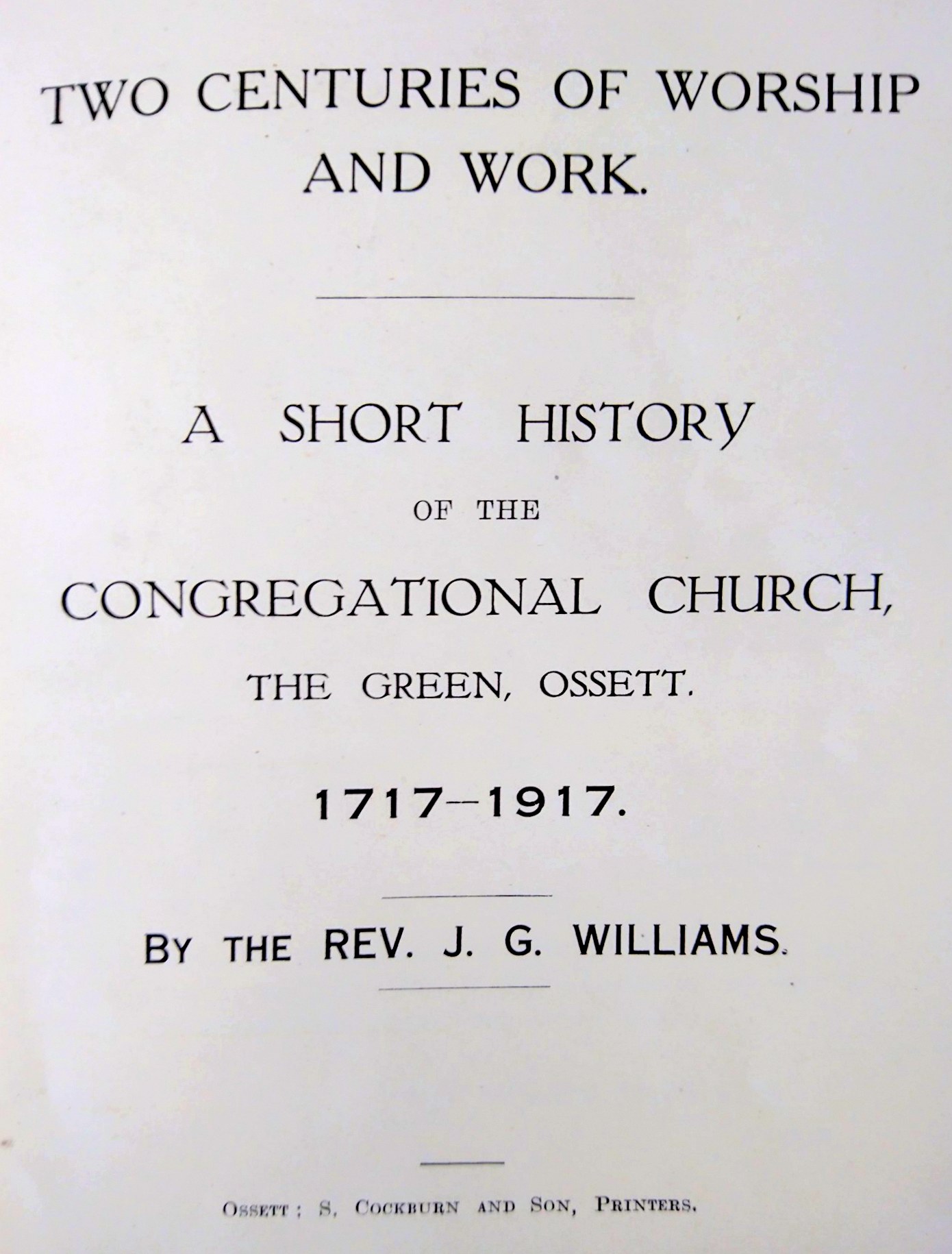

In 1917, the Rev. John Gomer Williams, minister of the Ossett Congregational Church, compiled the most erudite history of his church to commemorate it's bicentennial. Due to the tragic events of that war year, the celebrations were curtailed, the proposed new building was not constructed, and the planned new choir stalls were not placed.

His excellent book, ''Two Centuries of Worship and Work'', remains as a memory of that bicentennial that now seems so far away.

In Ossett today there are many places of worship with different forms of service, expressions of Christian faith, and the citizens of Ossett are completely free to go to any of these churches or none, omit their existence or follow the creeds and practices of any of them according to your personal preferences, conscience and conviction without restraint or hindrance.

In 1717 the situation was very different. Ossett was a semi-agricultural town of hardworking people who lived by making cloth on small scattered farms.

The Calder River was an unpolluted stream from which fish were fished, and on the main street, untidy and unpaved, was the prison, the stocks and the village church. There was no school, and only on rare occasions did a child make the daily commute to elementary school in Batley. One of them was Benjamin Ingham (1712-1772). There was a place of worship: a chapel with a priest provided by the Dewsbury Parish Church and the people were expected to conform to the Church of England.

Nonconformists, whether dissident Protestants or Roman Catholics, had suffered severe persecution for many years. However, there were groups of dissenters around Ardsley, Alverthorpe and Wakefield. They were Presbyterians.

In 1717 they decided to establish a meeting place at Ossett, Mr. Richard Foster (c. 1648-1730) lent his pressing shop for their services, and his son-in-law, the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743), a Presbyterian from Northowram, successor to Oliver Heywood (1630-1702), went to preach his first sermon.

At some point in the early years, these Ossett dissenters established themselves as Congregationalists or Independents. It was probably more convenient for the group to run it's own affairs than to be tied to the Presbyterian form of Church government. It's ironic to remember that the union with the Presbyterians, so close at that time, took 250 more years to achieve.

It's difficult for us to realize how much courage and determination was required of these founding fathers. Conformity with the Church of England, it's beliefs, and the liturgical form of service was expected, but on May 24, 1689, freedom of public worship had been recognized by the Act of Tolerance.

The Act allowed freedom of worship to nonconformists who had committed to the oaths of allegiance and supremacy and rejected transubstantiation, that's, Protestants who disagreed with the Church of England, such as English Baptists, Congregationalists, or Presbyterians, but not Roman Catholics. Nonconformists were allowed to have their own places of worship and their own school teachers, provided they accepted certain oaths of allegiance.

Dissidents were asked to search their meeting houses and were prohibited from meeting in private houses. Dissident preachers were required to have a license.

Thus, these dissident Protestants could have their own services in their own buildings, but nothing more. They were excluded from all civilian and military appointments and could not enter the universities. It would be more than a century before these disabilities began to be eliminated.

In 1703, Queen Anne (1665-1714) received this delegation of dissident ministers who presented their declaration of loyalty at her accession. He received them with grave discourtesy, in total silence, for his personal loyalty to the Church of England was genuine and sincere, but highly intolerant. She deliberately encouraged legislation that closed academies where dissident ministers were trained, and another law required all teachers to have a bishop's license.

These harsh laws were discussed when George I of Great Britain (1660-1727) came from Hanover to claim the crown, tolerated only because it would uphold the Protestant succession and drive away the Catholic Stuarts from the throne. It was undoubtedly appropriate to grant this pardon to dissenters. Perhaps it was this slight relief from restraint that encouraged the founding of the maverick cult gathering place at Ossett in 1717.

After 1717, meetings in the pressing shop continued with the help of the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743), Mr. Joshua Dobson, and other preachers until two years had passed. Then, in 1719, Mr. Samuel Hanson agreed to be the regular pastor and received the Hewley Fund 1728-9. The congregation was small and the stipend must have been small, because we are told that "Mr. Hanson was engaged in agricultural activities during the week." He left Ossett in 1730 and was followed in 1731 by the Reverend Thomas Lightfoot of Long Houghton, who herded the little flock until his death in 1758.

During Mr. Lightfoot's ministry, a chapel was built and we are told that "in 1733 subscriptions were opened for the construction of a Congregational Chapel at The Green, Ossett. John Fothergill, Richard Foster and forty-nine others contributed £ 51.11.0 together. " This seems like a very small sum to us, but we must remember that these people were not extremely wealthy and in 1738 a carpenter, for example, would receive a shilling a day.

The amount raised must have been enough to build the chapel. "It was square and barn-like. The singing was accompanied by a bass cello. The benches were of the high-back type and some were twice the size and occupied by the older people in the congregation or by those with large families." Stables were provided for the horses.

A deed of trust drawn up in 1737 stated that the trustees will seize a piece of land in Southwood Green with the premises erected there "with the intention and purpose that said chapel or meeting house be used and always employed as a place of worship by Protestants dissenters who resort there to hear prayers, sermons and other religious duties and for the ease and necessary reception of the congregation and for no other use, intention or purpose."

Under Lightfoot's long ministry, the Chapel on The Green became the religious center of a large district, and people came from Dewsbury and Thornhill. The poorest would come on foot and the richest on horseback, bringing wives or daughters behind them.

They were difficult years of change, restlessness and anguish due to England's long war with the French, and in 1795, the Reverend Thomas Taylor took on the great task of continuing the work in Ossett and during this same pastorate it was decided to modify and expand the chapel original.

Origin of names in Antiquity

In England there are around 45,000 different surnames, each with a history behind it and the sources from which the names are derived are almost endless: nicknames, physical attributes, trades, and almost all objects known to mankind.

In practice, tracing a family tree involves looking at lists of these names to recognize our ancestors.

Before the Norman conquest of Great Britain, people did not have hereditary surnames, they were known only by a personal name or nickname. Many individuals and families have changed their names or adopted an alias at some point in the past.

When communities were small, each person was identifiable by a single name, but as the population increased, it gradually became necessary to identify more people, leading to names such as Richard the Older, John the Younger, among many more, although over time many names became corrupted and their original meaning is now not easily seen.

After 1066, Norman barons introduced surnames into England and the practice gradually spread.

Initially, the identifying names were changed or removed at will, but eventually they began to stick and be transmitted. So trades, nicknames, places of origin, and parents' names became fixed surnames.

Many individuals and families have changed their names or adopted an alias at some point in the past. This could be for legal reasons, or just on a whim, but it points to the fact that while the study of surnames is vital in family history research, it's all too easy to overemphasize them.

Your last name may be derived from a place, like Lancaster, for example, or an occupation, like Weaver, but this is not necessarily relevant to your family history.

Thus, you can see that only by tracing a particular family line, possibly from the 14th century or beyond, will you discover which version of a surname is yours. It's more important to note that both surnames and first names are subject to variations in spelling, and not just in the distant past.

This website is developed by Westcom, Ltd., and updated by Ezequiel Foster © 2019-2022.